*********************

I want to get to know you better. Please fill out a 5-question survey at lizsumner.com/survey. Let me know when you’re done and I’ll send you a coupon code for my online course, 8 Steps to Launch Your Dream Life. (launchyourdreamlife.com)

*********************

Opening Remarks

Hi everyone, and welcome. One of the things I find fascinating as I interview people is the variety of things that attract us, how different are the subjects we want to learn, and the environments we want to explore. And how what scares one person makes another one come alive.

Jill Heinerth and I both love the water. We’d both jump on a flight to outer space if the opportunity presented itself. But Jill has trained to be a world class underwater explorer and boldly goes where no human has ever ventured. She faces her fear regularly and has taken away a lesson that I wholeheartedly agree with– that stepping into the darkness might feel scary but it’s also exciting. If you focus on that and take small manageable steps you can come up with some amazing results.

One of my favorite parts of my conversation with Jill is how she learned to say no. Once in awhile she finds herself in a situation where her professional judgment tells her this is unsafe. Even though she’s close to the prize or others want her to go on, she knows it’s too dangerous and draws the line.

For most of us our decisions aren’t quite as much a matter of life and death. But from time to time we all need to resist social pressure and respect our our personal boundaries. Sometimes saying no is as courageous as diving into the unknown

I encourage you to visit the links in the show notes and see some of Jill’s videos. Her descriptions are excellent but the images take you to a whole new world. Here’s the interview.

Transcript

Liz: My guest today is Jill Heinerth a fellow of the international scuba diving hall of fame. Jill is an underwater cave explorer, best-selling author photographer, speaker, and filmmaker. She joins us here from her home near Ottawa, Canada. Welcome Jill.

Jill: Thanks. Nice to be here with you.

Liz: You have many talents, which came first, the diving or the filmmaking or the science?

Jill: Well, I suppose my entire career has a bit of an accidental combination of many different loves in life. So, I mean, as a child, I always loved the water, but, in terms of education, I’m formally trained as a graphic designer and that was my first career in life before becoming a full-time underwater.

Liz: Wow. Okay. So how did you get from graphic design to underwater exploration?

Jill: As I mentioned, I took, you know, graphic design and fine arts in university, but I was also a scuba diving instructor and that was my hobby, my passion, and you know, a few years down the road in the advertising business, I thought to myself, you know, I love the creative process.

But I want to do it under water in the environment that I love more than anything else. And so, you know, I didn’t really know how one becomes an underwater Explorer or an underwater creative person. So I just sold everything and thought, I don’t know if I’m going to do it, but I’m going to slowly, March towards that, that goal of being creative under water.

Liz: Wow. Well, I, I commend you. I love courageous leaps like that. So, so what, what were the steps that you took?

Jill: Well, I mean, first it took a lot to become a scuba diving instructor, but certainly after my first scuba dives, I, I knew that was the environment that I wanted to be in. And so I always tell people, you know, ask yourself, where are you happy?

What space makes you happy. And I knew for me working inside in four walls, wasn’t going to do it. So I think that was the greatest realization first was that I couldn’t do like what I love to do in the space that I was in. I needed to be outdoors. I needed to be engaged in the environment. And honestly, it was a couple of years of process to, to think of, you know, selling everything and just kind of starting over, but, but once you do that and you’re going to land in a new place with just a suitcase in hand and no chance, but to succeed in your goals, you can kind of force that narrative to, to move forward.

Liz: So you went to become a professional diver. Is that what your path was?

Jill: Yeah, I was the scuba diving instructor and I sold everything in Canada, packed my bags and I moved to the Cayman islands to work at a small resort, just so that I would have focused concentrated time underwater. And it was there that I thought, okay, work on my underwater camera skills, working on my storytelling, pitch some stories to magazines, start to meet the right people who, might give me a little bit of an introduction into the film and television world.

And today my career is made up of a lot of different activities. I mean, one could say, well, she’s a writer or she’s a photographer or filmmaker. But all of those happen in this underwater environment.

Liz: Okay. So what about the caves? Cause you can be underwater without going into really dangerous places. Tell me about that.

Jill: Well, I’ve always been fascinated by caves, even as a child. I loved to sort of roaming around the Bruce Trail and Ontario, Canada, and walking through these crevasses and little cavern environments. And , I suppose, for me, those, those tight dark spaces are almost a back to the womb kind of experience.

I mean, I know it terrifies most people and would make them feel claustrophobic. But for me, there’s a very interesting feeling that I get from being in these spaces. And when I finally had a chance to dive in an underwater cave, I just went, oh, wow. You know, I don’t have to climb. I don’t have to use, you know, bolts in a wall to move up an environment, fight gravity. I can just inhale and move through this three-dimensional sculptural space. And I knew immediately that this was something I wanted to explore further. And so many, many years of, of training ensued and exploration along the way to, to build this career I have today.

Liz: And what, what is it that makes underwater cave diving so treacherous.

Jill: Well, imagine you enter the water, which is, you know, scuba diving is dangerous enough on its own because you’re reliant on life support to maintain yourself. But now imagine yourself in a place where you cannot swim to the surface if something goes wrong. So I’m literally swimming into an overhead environment and there’s no mission control to call for help to just say, get me out of here. You’re left to your own devices, your own equipment redundancy to deal with any particular failure you might have in your life support equipment. Now add to that some very difficult environmental conditions. There’s high flow, like a current in the water. There’s silt that’s easily disturbed by your own swimming movement, or even by your bubbles striking the ceiling of the cave. Certainly there’s opportunities for the geology within the cave. Divers also get lost in the maze, like passages of these environments. So there’s many things that can go wrong, but if you’re properly trained with the right equipment and diving within your experience and background, then probably can, can manage most what could come your way

Liz: Do you do rescues as well? I’m thinking of like the boys in Thailand, the soccer team that, that got trapped. Do you, do you participate in things like that as well as go for the beautiful nature shots and films?

Jill: Yeah. I mean, cave diving is still a quite small community, certainly with the very experienced practitioners. And so many of us, including myself, are involved in rescue and recovery operations.

When something terrible goes wrong, it’s a volunteer situation. Something that we do for our own community of, of, friends. So yeah, I’ve been many times to, to participate in recovery operations. It’s almost never, a rescue like happened with the boys in Thailand.

Liz: That was, that was amazing.

Jill: I was actually in Greenland when that happened and I was filming for a documentary and I was unable to go, and drop the job that I was working on, but it was all my friends that were involved in that operation and they did just the most incredible, team effort to to make that a successful risk.

Liz: Yeah, that was, that was very moving. So you, you dive in all kinds of different water that cold and warm. Tell me about the differences.

Jill: I live in Canada. So a lot of what I do is cold water. But I’ve dived inside icebergs in Antarctica underneath the Sahara desert, in the middle of Siberia, inside volcanic lava tubes in the Canary Islands, many different environments, as well as, you know, open ocean environments, lakes, rivers, wherever I can get wet.

Liz: Under the Sahara desert?

Yes. Yeah. I led a National Geographic project there many years ago.

Liz: What’s under the Sahara desert?

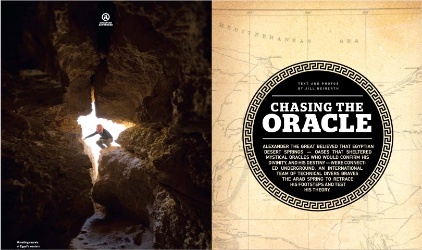

Jill: So this all started with my curiosity. I mean, as a child, haven’t you ever thought about it? Well, there’s these little pools, these little oases in the desert with Palm trees and dates. And how, where does this water come from? It only rains there once every 25 years. So, so what is this water? So I started digging a little bit deeper, ended up. Reading about Alexander the Great, if you could imagine, because he made a journey across the Sahara desert to consult with an Oracle and that Oracle turned out to be a well inside a temple on the Libyan border with Egypt.

And I went to that temple. I found the well, and I saw that clear water at the bottom and Alexander even wrote about how these oases were connected to, and I thought, are these caves, you know, I need to find out.

Liz: Oh, wow. And so is there a film, or did you write about that? Listeners will want to hear the rest of that story.

Jill: So I, I did write about it in many different magazines, no film yet. I still think it’s an amazing story. Yeah.

Liz: Do you have a link that we can put in the show notes about that story?

Jill: Yeah, I can, I can find that for you.

Liz: Sure. Yeah, good. I would love that. And, and I want to make sure that we put links to, to your book and to films because audio doesn’t do justice to what you’ve created. I’ve looked at your website.

Jill: You need the pictures.

Liz: Yeah definitely. So tell me about your book.

Jill: So I have two books. I have an adult and a children’s book. So, my memoir is called Into the Planet: My Life as a Cave Diver and it’s you know, stories of my expeditions and travels around the world, including, you know, going to Egypt.

But it’s really about fear. It’s about how we feel and embrace or run from fear, how it can really define your life moving forward. So, it kind of ended up being a bit of a motivational story for these times, as we all sort of face the darkness, the uncertainty of, of these COVID times. , you know, I wrote it before this all happened, but it really did end up resonating with a lot of people.

In terms of the challenges that we’re meeting today.

Liz: So some of my listeners listen, because they want an encouragement to try things that they haven’t ever tried. So what kinds of things do you say to, to people to get over? Just the, oh no, I’m too old. I can’t do that. It’s too late. That kind of result.

Jill: Well, you know, I think a lot of people face, fear or doubt, you know, when they. Like, oh, I wish I had, I wish I could have, or I’m too scared to, and I say to them, you know, I think that fear is what drives society forward in discovery and exploration. So, you know, when you feel that that, you know, twitter in the bottom of your stomach, that, you know, lets you know that you’re scared. It’s actually telling you something’s new. I mean, think about, you know, even just getting on a roller coaster or something, that’s much more benign, you feel that same feeling in your stomach, but you turn that fear into excitement. And we can do that with anything because when we step into the darkness, I mean, for me, it’s swimming into a cave, but when you step into the darkness of anything that’s new, whether that’s, you know, putting a proposal on your boss’s desk or trying some new activity on, the fear is telling you that you care about the outcome. And ties you to a desire for positive. Yes. And if we step into that darkness, and let our eyes adjust to the light, then we have an opportunity to do something very exciting, something that’s new for us, or maybe even new for humanity. And so you just take these small manageable steps towards that.

And before you know what you’re doing, something that you never imagined, and it’s really exciting.

Liz: Yeah. A former teacher pointed out something which I remembered. And that’s the physical experience of anxiety is basically the same as excitement. Yeah. So it sort of depends on what you name it.

Jill: Yeah. I mean, it’s like the word failure.

I don’t like that word. I like to call it discovery, learning. Because, I mean, the light bulb wasn’t, you know, invented on its first run, right? So it wasn’t a failure. No, it was a series of discoveries, progressive learning that, that finally resulted in something that has changed the life of everyone on this planet.

So. Forget about failure. I mean, you can think about what’s the worst possible outcome of my choice. Like what could possibly go wrong? And you can work through those things and say, well, it’s worth taking this risk, you know? I I’m doing it because it’s worth it. And then if the result is what you would have previously determined as failure, just say, no, you know, I’ve just learned something and I could try this again.

Or maybe I learned that I don’t want to try this again, but you’ll never know if you don’t try.

Liz: Yeah I absolutely can see that in many, many things, however, cave diving. I mean, like there there’s some– experimenting with cave diving has consequences that, that just learning to sing doesn’t have.

Jill: Yes, but we still take small manageable steps.

So training is very important. The right gear is very important. Continuing to develop and stay current is very important. Those are all small, you know, manageable steps that we can take. Like if, you know, for a long time you haven’t been able to do your craft, then you have to step back into it slowly.

And, and so these are all calculated risks. So every time we take a risk, we think about, you know, what’s the worst that could happen, but also how might a problem affect me or my family and my community, whatever. So, you know, taking a risk as far beyond yourself. It involves– I have to think about my husband when I go on a cave dive. Like is this something that’s a smart choice for both of us.

And you know, I know people may look at cave diving and say, oh, well, that’s frivolous. That’s that’s adrenaline-seeking sports. That’s adventure. You don’t need to take that risk. I don’t take that risk for adrenaline. It’s that’s not what drives me forward. I take these risks because of, you know, valid collaborations in science with other scientists.

I extend their eyes and hands into an environment that they can’t get to safely. So there’s always a reason for me to go to a place. When I go into a cave, it’s like going into a museum of natural history, except that nobody’s ever documented the assets within that museum. And I’m there to do that for the first time.

Just setting eyes on a place that nobody’s ever seen before and bring back that information.

Liz: Ooh. Tell, tell me about some experiences of first time being in a, in a place that before that no human that you know of has been, and times when you were really afraid and overcame your fears. Tell me some stories.

Jill: Well, I’ve had some exciting opportunities, working with scientists from, you know, biologists studying the unique life within underwater caves to paleoclimatology who are interested in the actual geology that informs us about Earth’s past climate and the future. I mean, I’ve found the remains of ancient civilizations that have left behind artifacts and, even burials, inside caves.

So there’s so much. I see and explore, not to mention that these environments are also places where we test procedures and equipment devices that are intended for other remote environments like space. So it’s a huge privilege to go to a place that nobody’s ever been before. And in a way fills my childhood dream to, to be an astronaut, except I’m an aquanaut.

Liz: That’s wonderful. And is that the name of your children’s book?

Jill: Yes, my kid’s book is called The Aquanaut. Yeah.

Liz: Any other times when you were particularly frightened?

Jill: Oh, sure. I mean, I would be lying if I didn’t say that I’ve had some close calls in my career. I mean, I was inside an iceberg in Antarctica. I was the first person to ever cave dive inside an iceberg.

Nobody had ever done it before. So we didn’t have a handbook to tell us what to do or what we might experience. And we ended up experiencing some terrifying conditions. We had, ice calving and closing the doorway that we’d gone into. We were pinned down by currents that made it impossible or almost impossible to escape the clutches of the iceberg.

So I’ve had situations like that. I’ve also been inside a very small cave, you know, about the size of the space underneath your bed. Yeah. When a scientist panics and became the cork in the bottle, you know, preventing me from being able to get out. And so I needed to solve all the issues. We were facing a broken guideline, broken life support. A diver that’s panicking and stuck trapped in the underwater cave. And I have to go into that situation, knowing that I can deal with all of those issues at once and get us home safely, which is, which is what happened that day.

Liz: Wow. Is there anything that you will never do again because that, that is just too, too far.

Jill: Yeah. There were lots of expeditions that I say no to. And I think that that’s the ultimate rule of survivors. I mean, yeah. People might look at me and say, yeah, you’re a risk taker, but. Yes, but I’m also risk averse. So, you know, I, I don’t have a death wish or anything like that. So there are times when projects are pitched to me and I’ll say no either, you know, maybe this, maybe I don’t like the safety culture of the group.

Maybe I don’t feel that there’s enough support for us to do something the way I would think of as doing it properly. I mean, there are geographic spots on the planet that have big red Xs on that. I wouldn’t go to just because. Other risks, just getting there, you know, getting kidnapped. I just turned down an expedition last week that involved, having to fly through Yemen.

And I’m like, nah, especially during COVID times, you know, I don’t want to spend the rest of my life trapped on an island off Yemen or, or, you know, kidnapped in an airport in Yemen. So I have to think about all those sorts of things. I have to think about those. Those risks in and out of the water, I have to think about cultural issues.

And so, yeah, there are lots of times when I say no, but I also think that it’s important to know when to abort something. So, you know, I might spend a lot of money to go to the far ends of the earth to do a project that’s very, very difficult. And then in the moment, like I remember being in Lanzarote in the Canary islands inside a volcanic lava tube, it had taken a lot of money to get there, to set up the expedition.

And I’m on the water’s edge when my rebreather, starts acting funny. That’s my life support equipment. And I literally turned to my partners. I’m sorry, but I won’t be getting in the water today with this. And they’re like, you’ve got to, we need this footage, we need this, we need that. We need to collect these animals.

And I’m like, sorry. You know, I’ll do my best to fix it. Maybe I’ll be able to dive tomorrow. But, but no, I have to know when to say no, or I need to even go on a dive and then be within just arms reach of what I perceive as success, like reaching out for the treasure chest full of gold and gone, “Nope, not today. I need to turn around. I only have so much life support gas left.” So knowing when to turn around is just as important as knowing when to say no. And assess those risks constantly.

Liz: I really acknowledge you for that. That is, that’s a hard thing to do, I think, particularly for women. “And let me do, let me just go a little bit further because you want me to.” To be able to, to recognize your own safety and, and choose in that moment for what you think is right. That is a hard thing to do. And congratulations.

Jill: Well, you know, it wasn’t as easy when I was younger, frankly. I mean, I think some of that is the wisdom of aging. I’m 56 years old right now, but, but the same, same girl in her thirties was a whole lot more likely to take on an additional risk because of that social hierarchy within an organization or an expedition.

I mean, It’s I’m sure it’s clear to most of your listeners that, that I work in a niche within a niche, within a niche that are all male-dominated and, and so fighting my way through the ranks to be, you know, regarded as a world-class explorer was not easy. And, you know, there are times as a young woman when I did just follow along with the group.

And I now recognize that I was taking risks that could have injured or killed me or maybe even one of my teammates. And so there was a certain amount of luck to get to me to get to where I am today. But there is that wisdom in aging, maybe a greater sense of our own mortality. Maybe, maybe just a confidence where it’s like, “no, I don’t think so.” That’s something I might not have said in my thirties. But you know, I encourage people to find that wisdom earlier, if they can. I mean, you’ll lead a whole lot more rewarding and fulfilling life if you do. And, and I also learned that when I did stand up for myself, sure. Some people got in my way, but that was about them. Not about me. I did lose some opportunities, but those were people I probably didn’t want to work with anyway. That was about them. It wasn’t about me. So yeah, I am the only one responsible for my own safety and choices.

Liz: That’s nice. Do you work with your own team or do you put a team together for each project? Who do you generally work with?

Jill: So I am an independent entrepreneur in a sense. So sometimes I’m creating projects and expeditions that I bring people into, but at other times I get calls from National Geographic or a television network or the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, or even an educational institution because they need my skills as a photographer, as a writer, cinematographer, as a consultant. I work for private companies, sometimes testing life support equipment, survey equipment, things like that, but really I am an entrepreneur, and so I do control my own schedule and choices, but, but you know, there are times when I take on long-term contracts with, with organizations. so it’s, it’s a really mixed career. It means, I don’t know where the paycheck is necessarily coming from, but I have control over what I get to do and the choices that I make.

Liz: How, how many projects do you do in a year? Generally in a non-COVID year?

Jill: Oh yeah. I mean, it really varies. I mean, you know, sometimes I’m just writing articles or that, you know, may take a few days or a week or, or I’m writing a book that takes years.

Sometimes a movie project can take three years to shoot a documentary footage for, you know, something of a Blue Planet level, project. So, so, it really varies year to year. Sometimes I’m doing more that’s generated solely by me and I, I fill in the gaps in my schedule creating, you know, assets of my own.

And then other times I’m working for, you know, a Hollywood company on for eight months on a movie, quite a bit of variety.

Liz: Can you tell us some of the things that you have up coming?

Jill: Oh, yeah. I mean, like everybody else in COVID times, things are shifting constantly. So when COVID hit and, you know, March 2020, everything I had on my calendar disappeared in the course of a few weeks.

So some of those have come back around to be rescheduled and then disappeared again. So I’m doing a lot more work in, in Canada these days, I’m working on a major educational initiative that supporting three documentary films about the great lakes. I’m working on some diving stories out in Newfoundland, Canada.

I still have some things kind of hanging on the books, like some work in Micronesia if the country opens again. Yeah. It’s so there’s a lot going on. I still have another book to write for Penguin Random House. So I’m plucking away at that and a new children’s book for Tundra. So yeah, they’ll, they’ll always be writing and photography for me one way or another.

Liz: Is there any dream place that you’ve wanted to explore that you haven’t?

Jill: Yeah, you know, I have not been to the Galapagos islands or Cocos. Those are two underwater places I’d like to go. I would like jump on a ticket to Space in a heartbeat. ,

Liz: Yeah

Jill: At the same time. I don’t really think of those as bucket list things.

I mean, every day I kind of pinch myself. I, I am, you know, very fortunate and rich with experiences, you know, living in Canada. And if I never was able to, you know, leave my own community, there would be a world of exploration for me to do right.

Liz: Wow. That’s great. So if there’s a listener who has experience as a scuba diver and wants to know steps to take it to the next level. What, what resources, what, what would you recommend?

Jill: Well, when people learn to scuba dive, they get a license, essentially a certification that they earn and it’s called open water diver. Well, that’s just the very first step, but for most people, that’s all they ever do. So there are many continuing education opportunities and diving like advanced diver rescue diver.

You know, those are the first two important steps so that you can kind of move from being only focused on yourself to learning more about the environment, to expanding your sphere of awareness, to include the awareness of others like in rescue diving. And then there’s, you know, the professional track, you can take the dive master and instructor.

But, cave diving as a part of what we call technical diving. Technical diving really means that you just can’t swim to the surface directly. You have to be able to stay underwater and solve your problems. And so you learn to carry additional tanks or you learn advanced life support systems. You learn new environment.

And, and those are, you know, many, many classes it’s not a fast process. Years of, of training is important, not just training, but also experience in new environments.

Liz: And what about photography underwater? What does one need to know to translate being a good photographer on land versus being it underwater?

Jill: Well, I, you know what, when I learned to use a camera as a young woman, of course we were shooting film. And when I first jumped in the water, I had no training and underwater photography and very quickly learned. This is completely different. All the things I’ve learned about composition that was applicable, but the technicalities of shooting underwater is very, very different.

There’s a class that you can take to just get yourself started and underwater photography, but, but I was completely self-taught and then of course, shifting into the digital realm, that was another, you know, hurdle. So, The best advice I can give to people, two things “F8 and be there” and shoot a lot.

The only way you’re going to become a good underwater photography is to shoot, shoot, shoot in different environments, tough environments, places where you think there’s nothing to shoot. You got to learn to shoot when you can hardly see underwater and, find, you know, find the story and, just keep doing it.

Liz: That’s beautiful. What would you like to say in conclusion?

Jill: I guess a couple of things.I f you want learn and more about what I’m doing then check out my website at intotheplanet.com. I’d like to leave the listeners with just the encouragement to, to go out and explore, find something that you’ve never done before that you’ve always wanted to do.

And it can be something simple. It could be knitting or it could be bungee jumping, or it can be, “I’m going to start a new career or I’m going to go back to school.” Look at that goal and start to think about the small steps that you could make in that direction. You know, what, what could you do to get yourself closer to that goal?

And just keep stepping a little bit further into the darkness to see if it suits you and see if the any risks are worth it, because I guarantee you the reward, the success will be very worth it.

Liz: That’s beautiful. Thank you. Thank you so much. That’s a wonderful closing. My thanks to Jill Heinerth.

You can find out more about her and her book and her adventures in the show notes. I invite everyone to write and tell me what you’ve always wanted to try. I’m Liz Sumner reminding you to be bold and thanks for listening.